There is something special about travelling through the night by train. It is the feeling of movement in the darkness. The twinkle of light in unknowable towns and villages across a blackened field. A subdued carriage, reflected in its own window. And it is the promise of adventure that comes from stepping onto a train from a platform in one country and stepping down, the next morning, into another.

Some readers will already be rolling their eyes at this point, at which is simply fair to say that the night train – and perhaps the whole premise of what is to follow – is simply not for you. But for those souls who still get a shiver of delight when seeing some far flung destination on the departures board of the station, as the last of the commuters are making their weary way home, it is a romance that has just about endured for more than a century and a half.

***

It began with the most modest of innovations and grew into something that linked nations and spanned continents. Some argue that the earliest example of a sleeping car appeared as early as the 1830s, linking London with Lancashire and the opportunity to climb aboard a “bed carriage” as the train rattled through the night. The first true sleeping cars hit the tracks in upstate New York in 1857. And then came George Pullman and his Pioneer, with luxury carriages that were taller and wider than anything that had come before, using trucks with rubberised springs to reduce bouncing and shaking, and decorated with thick curtains and chandeliers.

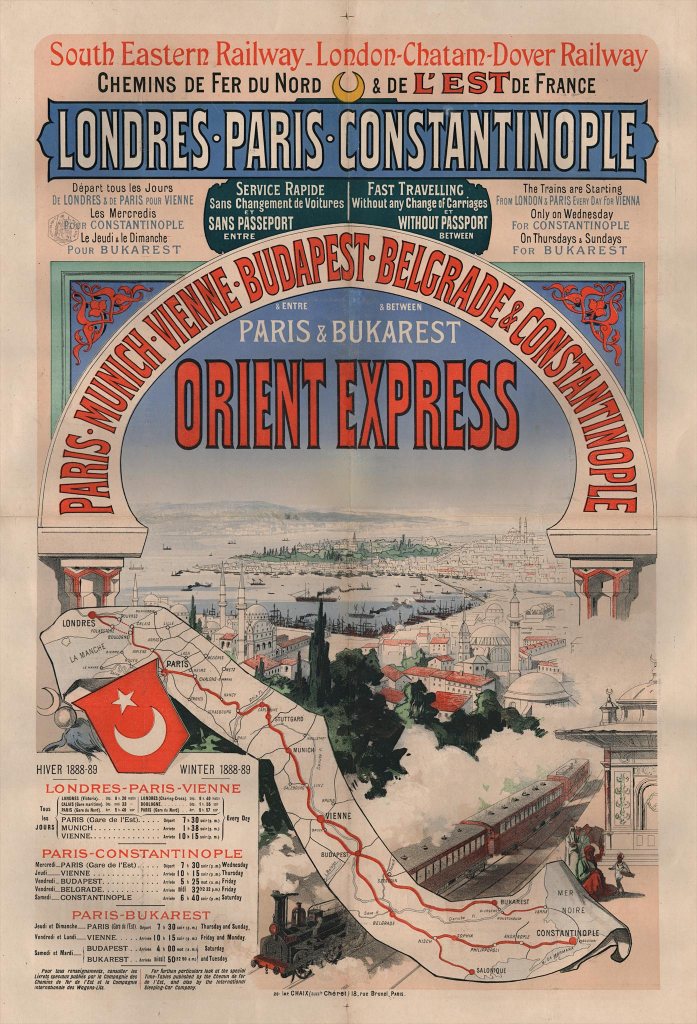

Pullman’s name would become synonymous with luxurious travel by train, but across the Atlantic, Europe was developing its own vision of high-end, overnight rail travel. In 1872, the young Belgian George Nagelmackers founded the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL), the first step in a vision of a network of luxury trains that would unite a continent. In 1883 the first Express d’Orient left Paris for Vienna, eventually extending to Istanbul, and would soon become the defining standard for what long-distance travel, and the sleeping and dining cars that would get you there, should look like.

These were moving palaces, carrying royalty and writers, actors and singers, diplomats and adventurers, and had a truly transformative effect on both the practicalities of travel but also perceptions of distance, culture and shared experience. But as the 20th century progressed, the romance of the night train faced mounting challenges. The rise of commercial aviation in the 1950s and 1960s, not to mention the development of high-speed rail networks, began to erode the appeal. Sleeping car services declined, budget airlines conquered the skies, and one by one the great night train routes began to disappear from the schedules.

***

For a while it seemed like night trains had had their day, especially in western Europe. For those of us in Berlin it was with sadness that we watched as Deutsche Bahn removed all their sleeper services. The trains that used to connect our city with Munich, with Villach in Austria, Trieste in Italy and Rijeka in Croatia disappeared from the schedules. These were all journeys that we had done. On night trains in a seat or a sleeper compartment, or on the old car trains that delivered not only travellers but also their vehicles. We had caught a train through the night from Warsaw, when my partner Katrin was too pregnant to fly. We’d had dinner in Paris and breakfast in Berlin. We looked forward to those journeys as much as the places we were going to.

And then it looked like it was all over. Night trains no more.

But just before the pandemic hit, it seemed as if things had turned. In Switzerland, the Netherlands, Czech Republic and – most of all – in Austria, it looked as if there was a real desire to bring new services to the timetables. Deutsche Bahn might still offer trains that travel through the night from Aachen to Berlin with only seats and no couchettes or sleepers (done and not recommended), but their challengers across the border were offering real night trains. Bed linen and breakfast rolls. A glass of wine at dusk. The romance of rail travel.

Leading the resurgence of night trains in Europe is Austria’s Federal Railways (ÖBB), with a Nightjet service that has expanded to over twenty routes. Although the pandemic put a pause on things for a while, the new services have survived and have been added to all the time. From Berlin we have been investigating trips to Switzerland and Sweden, to Budapest and beyond. The only problem right now is being alert enough to book your ticket. The services are popular, which can only be a good thing, so long as capacity is increased to meet demand.

***

It is here we should pause on our tracks to reflect a little on why night trains can and should be a central pillar in reducing the carbon footprint of our travel. That, if they are comfortable enough, and competitive enough in price, they are a far more desirable way to get from A to B than an early morning flight with airport queues at both ends. That the way things are at present is unsustainable even in the medium term, and that the time it takes to develop new routes and networks, to build new carriages and get them on the tracks, requires action now and that there is no time to delay.

And this is all true. But like so much of the discussion around travel, tourism, sustainability and the climate crisis, if you have read this far then you already probably know this. So what we are interested in here is something that is harder to grasp. Something that cannot be compared to alternative forms of travel in the way that carbon emissions can, or the price of a ticket or simply the time it takes to get to where you want to go.

Instead it’s about magic. It’s about adventure. And it’s about joy.

***

There was not much joy at Euston station as evening tipped towards night, but there was something special about the train on the platform. The main ticket hall was thronged with frustrated people. Signal problems and other delays north of London had caused chaos for evening travellers, most of whom were simply trying to get home, and the mood was a mix of anger and resignation. But down on our platform, it couldn’t have been more different. As the train waited on the tracks and the passengers moved along its length, trying to find the right carriage, the prevailing mood was one of gentle excitement.

There were men and women in suits, heading north after long days working in the city. Some were clearly regulars, greeting the guards like old friends and discussing what time they would meet in the dining car. Familiarity did not seem to dampen their joy for the journey ahead. Others were dressed for other adventures, such as the small team of climbers who loaded their gear from the platform onto the train, making a chain to stow their rucksacks and duffel bags into any available space in their compartment. Some were like us, first-timers on this famous route through the night. The Caledonian Sleeper. Just the name alone was enough to trigger the imagination.

While the crowds still waited in the ticket hall, we left on time, easing our way through the north of the city in the darkness. It was the end of winter, beginning of spring. The weather was on the turn, and the forecast for Scotland was good. Still, the guard in our compartment told us, we shouldn’t get our hopes up. Quite often the train had travelled all the way to Fort William and the only thing visible through the window was the darkness of England and a Scotland engulfed in fog. She was from Fort William, she continued, as if that should be enough to confirm her knowledge and experience. You couldn’t trust the weather. Not at any time, but especially not now.

We ate our picnic and drank a beer or two, before letting the gentle motion of the train rock us to sleep. Despite the romance, it’s not always easy to sleep on a night train. Often it is the stops that wake you, as you peer bleary eyed into the bright lights of Preston station. But still, sleep came, albeit fitfully, and in any case we were too excited about what we would see when we woke to stay in our beds too long.

We took our position at the window, sipping on tea and coffee while spooning our porridge that had been delivered to our compartment, as the train moved north of Glasgow along the water. Hills and towns, ships on the Clyde and, slowly but surely, the gentle rise of the land as we moved ever closer to Rannoch Moor.

This had been the goal, a place of high, boggy moorland ringed by low, snow-capped peaks, that had long captured the imagination. In the corridor a woman told us that this was the second time she had done this journey, and the first time she had seen anything. Last time there had been nothing but a wall of white beyond the window. The guard, who had joined us, nodded knowingly. But this time was different. This time the sky was mostly blue with high clouds, clear air and a view across the frozen expanse that invited single-word scribbles in the notebook that could not possibly do justice to the scene.

Bleak. Beautiful. Breathtaking.

Down below we caught a glimpse of deer and even a stag. They had come down towards the tracks in search of food. The train continued on, calling at lonely stations where our hiking and climbing friends dropped down and disappeared into the wilderness, striking out for adventure. It was all we could do not to follow them. But we wanted the whole of the experience, to take the line across the moor and down the valley, circling Ben Nevis and arriving in Fort William at the water’s edge.

In all her years, the guard said, she had never seen it like this. We were standing at the end of the carriage, looking out through the window at Ben Nevis. It was a long night, she conceded, but on mornings like this it was the best job in the world. Then she remembered herself. We had been lucky, she said, with a stern look on her face. You can’t always expect a view like that. This was Scotland, after all. Then she looked back out through the window, and you could sense the pride that she felt for what had unfolded beyond the window of the Caledonian Sleeper and that we had been along for the ride to see it all.

***

Was it a fluke? After all, to get Scotland in all its theatrical glory could give the night train a reputation it doesn’t quite deserve, especially when the guard itself had never seen anything like it. But the more night trains we take, the more it becomes clear that all landscapes have their own particular drama as they reveal themselves in the early morning hours and when combined with a journey through the night.

Take the Alps. It was our good friend Nicky who gave us the idea.

‘If you’re already taking the night train to Vienna,’ she said, ‘then might I suggest you book tickets to Graz? The price will be the same and you’ll get to spend the morning following the Semmering Railway through the mountains. You can always have lunch in Graz and then catch a train back to Vienna in the afternoon…’

It sounded like a plan. The night train from Berlin was due in to Vienna at 7am. By staying on board to Graz, we had the possibility of a lazy morning eating breakfast in our compartment rather than a bleary eyed stumble onto the platform. In one journey, we’d get to combine our love of the night train with a trip along one of the most famous stretches of railway in Europe, one which has been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

We travelled through the night via Poland and the Czech Republic, crossing the Oder in the gloaming before heading south through the darkness. Somehow we missed the stop in Vienna, sleeping through the kerfuffle outside our compartment door as most of the travellers on our carriage departed into the hustle and bustle of the Austrian capital. By the time we emerged from our slumber, somewhere around Wiener Neustadt, there were only a few of us left.

At this point, the landscape outside our window was distinctly flat, but soon the first lumps and bumps began to appear, as wooded hills rose either side of the train tracks. The Semmering Railway begins at Gloggnitz and crosses the pass to Mürzzuschlag. In Gloggnitz we could see the workers busying themselves at the opening to the new tunnel that would eventually displace this route for most freight and long-distance passenger traffic, but for now the tunnel remained just a hole in the hillside as we passed by and began the long, sweeping assent up towards the village of Semmering.

If you look down the train through the windows, especially on the stretch between Gloggnitz and Semmering, you can catch a glimpse of the engineering marvel that is the Semmering Railway. The train curves around atop beautiful brick viaducts before plunging into dark tunnels. All the while you are being lifted up and over the mountains; an altitude difference of 460 metres over the 41 kilometres between Gloggnitz and Mürzzuschlag.

Altogether we passed through 14 tunnels and across 16 viaducts and more than a hundred small bridges. We saw rocky outcrops and precariously perched buildings, farmhouses with balconies in bloom and the grand old hotels that attracted the great and good of Viennese society once the railway was opened in 1854. At Semmering the train stopped for a moment, alongside an old carriage of the Südbahn which once connected Vienna to Trieste and the Adriatic coast, back when it was still part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

As we ate our bread rolls and sipped our coffee, we were reminded of what this railway once was, and that however modern the carriages become, they will always hold in them the romance of the railway history upon which they are built (and travel). From Semmering it wasn’t long before we reached Mürzzuschlag. We continued south, following the Mürz until it met the Mur, the railway following the route the rivers had long carved out of the landscape until we reached Graz. It had been a memorable morning, and as we climbed down onto the platform, there remained some excitement in the knowledge that, in a few days’ time, we’d get to do it all over again in the other direction.

***

There is space for more stories. There is always space for more.

***

A dining car just outside of Berlin, as the night train began its meandering journey down to the Adriatic. The carriage was old, its upholstered seats craving at the edges and bare in patches. Plastic lamps on the tables offered low lighting. The food was solid but unspectacular. The beer was good. It was like a scene from an old film, with bearded motorbike riders squeezed in around the table in their leathers cast as the unlikely extras.

Years ago, before the border was softened by Schengen, crossing from Slovakia to Hungary. A seat in a six-person compartment, shared with a group of Czech women on their way from Prague to Budapest. The border guards and customs officials on both sides had woken everyone up, so it was time for an impromptu picnic in the middle of the night. There was no shared language, but plenty of shared food. Smoked sausage and bread rolls. Crisps and a cucumber peeled with a bread knife. Red wine and water. Vodka straight from the bottle.

Lifting up the shade on the way home from Paris. It had been a long trip, through Germany and France. It was the moment when you realise you just want to get home. The train made its steady progress through Brandenburg at early light. A sliver of mist hung over the rutted and ploughed fields. Smoke rose from the chimneys of a village beyond, low slung houses huddled around the church as if for protection. The only other movement, a sedge of cranes taking long, careful steps across the night-hardened soil.

A coffee shop in Trieste station. The only place open, as men in high-vis jackets hosed down the platforms and the concourse. All our fellow travellers had disappeared into the morning, but we weren’t ready for the city just yet. We stood outside and sipped our coffee as the sun rose above the grand buildings across the street. Somewhere near here, Nora Barnacle had spent the night, waiting for James Joyce. We could smell the Adriatic, mingled with exhaust smoke. We’d arrived.

***

These are, it feels safe to say as we near the end of this journey, moments that no airline can replicate and no motorway can deliver. The slow transformation of landscape. The gentle rhythm of wheels on the tracks. The community that forms in corridors and dining cars among strangers who are united in the choice to take the longer way, the slower way, the way that allows for serendipity and wonder. This is something we should cling to in this age of efficiency and speed. It is the luxury of time, the pleasure of the journey itself.

The joy of the night train lies not in getting from here to there as quickly as possible, but in savouring the journey between. In the magic of the movement through the darkness, the promise of waking up in someplace new serves as a reminder that the world is vast and its various and it is well worth taking the time to traverse it properly.

We just have to consult the timetables and book the tickets. Make our way to the station as the light softens and the darkness approaches, with midnight and the witching hour to follow. Shall we see where the night train might take us next?

Words by Paul Scraton

Photographs by Katrin Schönig